With novel treatments for Alzheimer’s disease dominating the headlines, the most recent being donanemab with the FDA requesting an independent advisory committee to review its safety and efficacy[1], questions remain about their clinical benefit. As the number of patients with Alzheimer’s disease in the US is projected to grow in the coming years, so does the need for a paradigm-changing treatment. However, our model finds that the new monoclonal antibodies offer little clinical innovation over the old standard of care, donepezil. Leaving aside price, their disadvantages in safety/tolerability and dosing outweigh their modest efficacy gains.

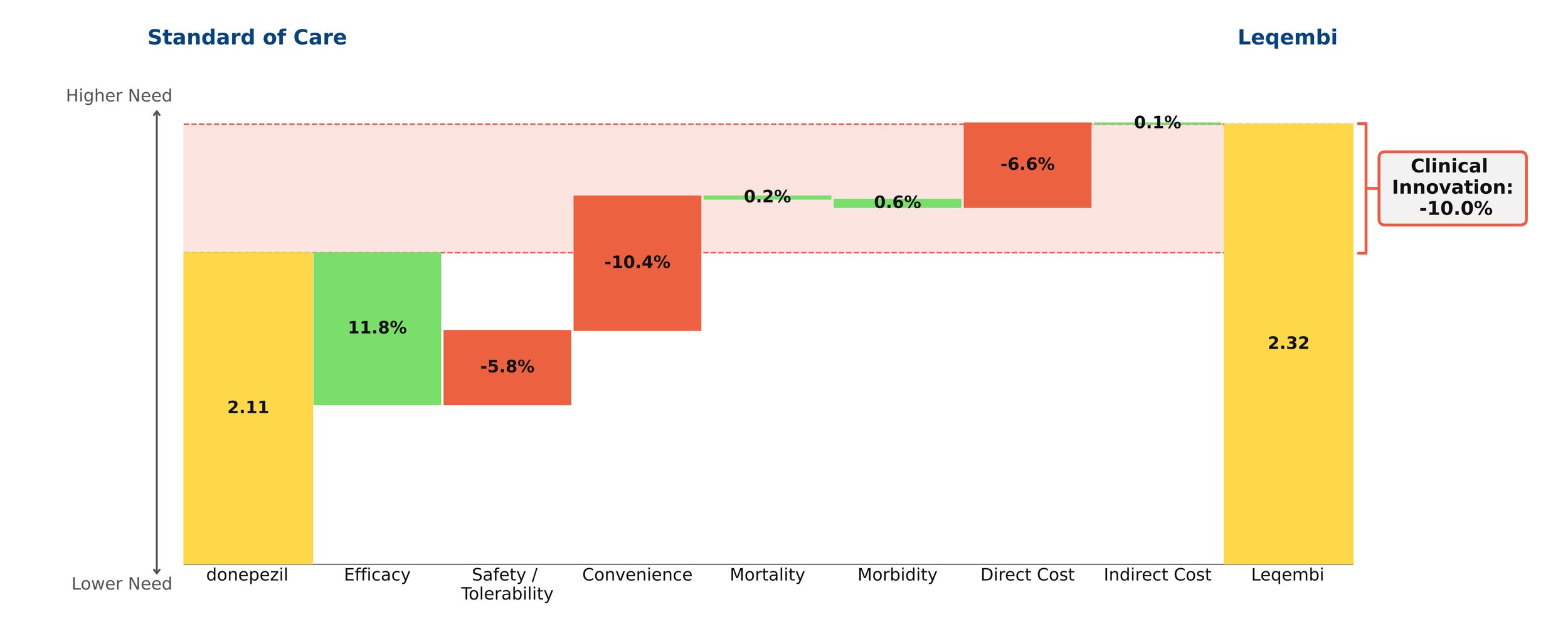

Despite remaining on the market, unlike its ill-fated predecessor Aduhelm, Leqembi shows negative clinical innovation over donepezil of -10.0% in our framework. This is little better than Aduhelm, which shows -11.0% clinical innovation vs. donepezil. As shown above, much of the negative clinical innovation is driven by convenience. Leqembi is given as a one-hour IV infusion every two weeks, compared with donepezil’s once-a-day pill. While Leqembi offers an efficacy benefit measured by standard measures of cognitive decline in AD, this pales in comparison to the inconvenience of the regimen, combined with high cost, high prevalence of potentially serious side effects and a black box warning for amyloid-related imaging abnormalities (ARIA). Questions also remain about how clinically meaningful the improved efficacy is: it is unclear how much patients and their families can appreciate a slowing in cognitive decline of about 6 months for the fraction of patients that experience it.[2]

Even though little separates Leqembi from Aduhelm in our framework, Leqembi has managed to achieve modest sales – around $10.1 million in 2023, still well below the original Eisai projections of $28 million for the year.[3] This is despite the fact that the Institute for Clinical and Economic Review (ICER) deemed its current annual WAC price of around $26,000 to offer low long-term value for money, suggesting a more appropriate price is around $10,000 annually.[4]

In spite of these equivocal results, in-class Eli Lilly drug donanemab was originally expected to be approved this year, with some analysts projecting blockbuster sales of more than $1 billion by 2025.[5] However, our model suggests donanemab will offer slightly lower clinical innovation than Leqembi or Aduhelm, owing to a poorer safety/adverse event profile and higher rates of ARIA.

Leqembi is currently trialing in subcutaneous form, as is donanemab. More convenient dosing would improve the outlook for these agents, but they will still face the headwinds of modest efficacy and significant safety concerns, as well as burdensome monitoring/imaging requirements. With all these considerations, it is difficult to believe that Eisai will hit its revenue target of $8.8 billion by 2032.[6]

[1] Edited to note 3/8/24 New York Times article

[2] https://memory.ucsf.edu/lecanemab

[3] https://www.biopharmadive.com/news/eisai-leqembi-alzheimers-target-revenue-earnings/706668/, https://www.pharmalive.com/eisai-sees-dramatic-increase-in-leqembi-uptake-following-full-fda-approval/, https://www.reuters.com/business/healthcare-pharmaceuticals/eisai-expects-alzheimers-drug-rake-revenue-665-mln-by-march-2023-11-07/